A great deal of attention gets paid to the creation of wealth, but not nearly as much is paid to its slow dissolution over successive generations. It would seem, however, that understanding the handful of ways great fortunes disappear would be quite useful to people who are planning for the disposition of those fortunes. In this series of posts, we have suggested that there are three basic patterns found in the “endgame” of substantial wealth: Division, Preservation, and Growth.[1] It seems that these basic patterns can strategically inform how estate plans are constructed and administered.

Making estate plans strategic – not just tactical – is a radical approach. Out of this mindset, the advisor can help a client determine which strategic path or endgame he or she would choose and what would be required to create a family culture that would permit that plan to be successful. The role of strategic advisor who works from a perspective of “endgames” moves the professional from being a technician helping the client solve complex tax issues – which are tactical – to becoming a trusted advisor who is helping the client work through difficult issues and arrive at wiser decisions than they would otherwise have adopted. This intersection between strategy, tactics and familial capacity potentially opens much greater clarity for both the advisor and the clients they serve.

The Endgames Revisited

The endgame of Division involves the simple allocation and distribution of assets to beneficiaries. Some assets may be placed in trust when beneficiaries lack the capacity to manage their affairs, but for the most part, under Division, the assets are distributed without strings, conditions or controls. It is left “outright and free of trust”. This approach is the staple plan of the mass affluent. It is rare, but not unheard of, in the plans of the wealthy.

When substantial wealth is involved two additional strategies come online: Preservation and Growth. In the game of Preservation, steps are taken to ensure that the patrimony lasts for as long as possible until it is eroded by the inevitable growth of the family and the demands placed on the accumulated capital by heirs. These plans expect modest growth and slightly above average market returns. The estate lasts for a few generations until spending and the law of large numbers renders the structure unsustainable.

In the current planning landscape, the vast majority of Preservation plans are driven by tax considerations. The idea is that the greatest threat to preserving wealth are complex issues of taxation and investment that are best handled by professionals. Plans may also attempt to control spending through the distributive functions of professional trustees. Plans based on Preservation scenarios can become quite complicated. In the game of Preservation, the family is rarely in charge of the wealth – such work is left to trustees, family office professionals, lawyers, and accountants.

The final scenario is the endgame of Growth. In Growth, the patrimony becomes a pool of capital used by the family to invest in the human potential of individuals and the collective engagement of the family in businesses and maintaining familial growth and harmony. The Growth scenario requires that financial wealth increases in each generation to keep the engine going. This demands growth significantly in excess of market returns which can be achieved only through the investment in and operation of enterprises. This, in turn, requires the intentional development of evolving collective competence and coherence of the family as managers of complex interlocking financial entities. Such families know how to start, maintain, harvest and reinvest in profitable enterprises. Like Preservation strategies, Growth plans avoid taxes but, unlike them, they place high demands on the effectiveness of the family both as individuals and as a collective in their capacity wisely govern and foster entrepreneurial capacity within the family. Few families are likely to know, with certainty, if they are truly in Growth scenario before the third generation.

The Role of Advisors

The endgames of Preservation and Growth come not only with legal structures that contain the wealth but also with a bevy of advisors to manage and administer those structures. In wealthy families, these “Formations” (the ongoing interaction of structures and advisory networks) become a dominant reality of family life.[2] Wealthy families, in practice, inherit not wealth, but Formations. Their relationships to wealth are mediated by structures (trusts, family offices, foundations, etc.) and by professionals (attorneys, trustees, investment managers, accountants, consultants). As a result, in wealthy families, the dominant organizing force for their familial relationships is often the Formation comprised of entities and the advisors who serve them.[3]

Listen to Sallie Bingham:

I did not understand for many years the elaborate system of trusts, like an underwater mountain range, which had been piled up years before to avoid paying estate taxes. Little thought had been given to the effect on the next generation. There was an unspoken assumption that money should be passed along, like jewelry and antique furniture, yet underlying this facile assumption was a great anxiety about money and its mystifying uses, money and its perverse connection with love….[These decisions were] made before any of us were old enough to wonder whether we wanted our unborn children to become millionaires…The mountain range of trusts lay in that deep underwater world where the big fish swam: lawyers and accountants who understood the territory but had little incentive to share their secret information. It would be many years before the beneficiaries of this mountain range understood that it existed and many more years before, I, at least, began to question inherited wealth. The mountain range walled us off from more than poverty.

Sallie Bingham’s evolving rebellion as a third generation heir pushed back layers of secrecy, advisory authority, and corroded family relations. Her unwelcome inquiry eventually resulted in her overt refusal to sign a buy-back agreement. That simple act of rebellion pulled a thread that led to the unraveling of the entire Formation a few years later. The story she tells of her family provides a graphic, albeit hotly contested, insider’s perspective on what can happen in wealthy families and serves as a cautionary tale for families and advisors alike.[4]

The Road Less Traveled

Success stories, while perhaps less plentiful, are not difficult to find. Families that thrive for generations develop a resilient family culture that serves to counterbalance the power of the Formation. For these families, wealth becomes a blessing, not a curse or a burden. For the most part, such families tend to avoid what Jamie Johnson referred to in his film Born Rich as “the voodoo of inherited wealth”. These families work to avoid the infantilization of adults that often attends families of great wealth. They also become skilled at ensuring that the brute fact of wealth doesn’t negatively dominate their lives by causing heirs to become dependent on the Formation. In these families, adult progeny rise to leadership positions within the family, in its collective businesses, and in the broader community. Such families have their share of drama, but on the whole, they are productive and competent. Most importantly, they manage to overcome the significant challenges of generational transition and gain the skill sets to work collaboratively to a degree that allows them to succeed together. Part and parcel of this is their ability to manage their advisors, rather than be managed by them.

Different Endgames, Different Skills

The astute reader who has followed along will recognize that each endgame requires greater skills and capacity than the one before it. To hang onto wealth in a Division scenario, the generation receiving that wealth must have financial fluency. That is, they must be good with money. Heirs must know how to save, share and spend in sustainable ways. They often will hold jobs and the amounts of inheritance they receive is not likely to result in demotivation or dissolution. Wealth will be healthy addition to their lives, not a debilitating anchor to their adult development. Wealth will tend to supplement but not underwrite their lifestyle. Those without financial fluency go through the money and are left with little or nothing. Some Preservation strategies grow out the recognition that beneficiaries without financial fluency must be protected from themselves.

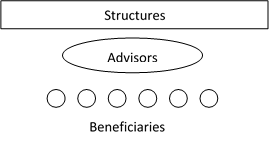

Between Division and Growth is the game of Preservation. This is the by far the most common endgame played by wealthy families. Most often this is an endgame that has grown from the tactical decisions described at the beginning of this piece – opportunistic growth of an estate plan based on tax considerations. The other impulse that can often drives these plans is a kind of paternalistic belief that the children must be protected from themselves. Here two options are theoretically available. We now introduce a new idea – that the endgame of Preservation can be played in one of two ways. The first is the default approach we have spoken of; that is, to turn the management of the accumulated capital over to professionals who will watch over a gaggle of relatively incompetent beneficiaries. Let’s call this Advisory Preservation. In some ways the advisors serve the structures as much (and sometime more) than they serve the beneficiaries. Accountability for the success or failure of the strategy lies with the advisory network. The power dynamic in these structures looks something like this:

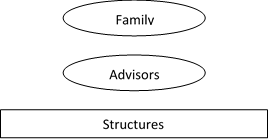

There is another alternative. Here the family is intentionally prepared to steward wealth wisely in collaboration with the advisors who serve the family, not the structures. Let’s call this Familial Preservation. The skill sets required for Familial Preservation include, at a minimum, financial competency, wealth competency, and governance competency. Not only must the family have the skills outlined above in Division, they must also be fluent with the legal structures that hold and preserve that wealth and know how to collaborate effectively with their advisors. They will, in effect, work with and through their advisors to accomplish familial outcomes. They must also be able to make collective decisions as a family and maintain familial dynamics that will nurture, not erode, the health of the Formation. Final accountability for the success of the structure rests with the family[5] and its capacity to work wisely together. In this plan advisors work for the family. The power dynamic in this approach looks more like this:

Note that these plans will be collaboratively designed across generations, will give the family much greater control over distributive functions and will view the structures as flexible tools to be used by the family to develop its human, cultural and social capital. The structures will be managed with and through advisors who are seen as working for the family, not serving the structures that have institutionalized their roles as protectors of the patrimony. Obviously structural limits may still exist, but the power dynamic is radically shifted under this model. This model assumes the development of real competence and capability of the family (and the individuals within he family) and the ability of the family to manage and develop itself over time. The goal remains the preservation of structures.

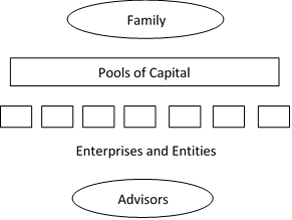

For the Growth scenario to work, the family must be good not only at managing money, and be adept in stewarding wealth and developing governance practices. It must also have the acumen and skill to build or invest in profitable businesses that will grow the wealth, and engaging in meaningful philanthropy, which paradoxically is a tool that most growth scenarios contain. Few families accomplish this, but there are those that do. The most important characteristic of this approach is that structures are viewed as pools of capital to be invested and deployed by the family in dynamic environments that require skill and creativity to navigate. Advisory network players change to meet the needs of the family structures as those structures evolve. This all requires a highly sophisticated set of skills (typically spread across different family members and branches). Such skills do not occur spontaneously – they are intentionally curated and developed over time. In Growth scenarios, every generational transition brings with it a geometric increase in complexity and its own adaptive challenges to be overcome. These are evolving, adaptive and developmental systems. This is not an easy path – it requires dedication, luck, intelligence, and real skill to become what the literature describes as an enterprising family. The power structures in these plans will look much more like this:

Of course, what is illustrated above is a set of “pure” cases. Actual estates and real families are usually hybrids of the above with elements of the various models cobbled together. Few wealthy families fall very cleanly into any one of these categories.

And therein lies the problem.

The Consequences of Tactical Thinking

If one looks at the typical estate plan of a wealth creator, the overall arrangement of entities has come together as a result of tactical moves usually driven by the desire to avoid estate taxes. A plan might include a living trust, wills, cascading GRATs, ILITs, LLCs, GSTs, Dynasty Trusts, a Foundation, a PTC and other structures from the alphabet soup available to skilled practitioners under the United States tax code. In large estates, these can also include substantial family offices. Each of these entities was put in place at a specific time to address certain threats or to take advantage of certain opportunities. Such plans are not strategic in the sense that they are not driven by a set of interlocking long-term objectives over and above immediate felt needs for reducing estate taxes and providing consolidated management. While such entities do evolve, they most often evolve in ways that ensure their institutional survival. In short they are formed subject to the primal contradiction, that is, “A strong individual leaves an organizational legacy that utterly fails to come to terms with the hard reality of collectivity.”[6]

The result of such plans is that the families that inherit these structures play out the endgame of Advisory Preservation by default, not design. Professional advisors are in the driver’s seat and hold both positional and informational power. Under this scenario, the Formation dominates the family as it did in the Bingham family. For most clients, this is their worst nightmare – that their children will become dependent on a mass of capital in ways that impede their individual growth and development into fully functioning autonomous individuals. And to add to that particular horror, they have paradoxically created a structure that will ensure that the government will be an intimate partner with their family (in the form of legal structures subject to tax compliance and the legal process) for generations.

It is worth noting that few families actively prepare to play the game of Familial Preservation. Under this scenario, the family, not its Advisors, actively govern the Formation. Setting the table for Familial Preservation to work requires that the family members not only manage their personal finances but that the family as a whole 1) develops expertise in the legal mechanisms of wealth preservation and 2) that it can work effectively with advisors and 3) that they gain skills of collective decision making. For this to work, the founding documents themselves must empower the family to make decisions and especially give them the power to hire and fire professional advisors (which presumes a degree of sophistication to tell when they are well or poorly advised). More importantly, these plans presume that the family can make collective decisions which, turn, requires that they develop a culture of effective collaboration. The implicit and explicit decision making processes that emerge can be called governance. Breakpoints in any one of these key skills – money skills, wealth skills and governance skills – can threaten the durability of the Formation.

Different Strategies for Different Endgames

Circling back to the question of strategic intent, the problem with estate plans that have grown by way of tactical responses to threats and opportunities under the tax code are frequently untethered from the more human strategic objectives of the first-generation wealth creators. If a client is philosophically committed to an endgame of Division (which many are), the introduction of a Generation Skipping Trust (GST) that will endure past his or her lifetime and into the lifetime of his or her grand-children is tactically congruent to that strategic objective no matter how advisable it may be from a tax perspective. A GST belongs only in Preservation or Growth plans.

If the client is driven to avoid estate taxes and wants wealth to be preserved, the planner and client are by definition “in” a Preservation strategy. If the client is committed to preparing the heirs or the heirs have the personal and collective capacity and capability to constructively benefit from a GST on a familial level, then Familial Preservation becomes a viable possibility. If not, the planner has to consider whether he or she is doing a disservice to the client and the clients’ family in creating an Advisory Preservation plan and if the client is informed as to what he or she is actually authorizing. Does the client really want the infantilization that most often comes when wealth is mediated by structures and advisory networks? If the GST runs the risk of creating long-term dependence and entitlement, then the client may have to think long and hard about whether that is truly the path he or she wants to go down, no matter how efficient that path may be from a tax perspective. When the client is not committed to preparing the heirs, and the family is displaying no inclination to work together, the client’s family will be saddled with a Formation managed by professional advisors – and will have defaulted to the strategy of Advisory Preservation. The client should know the downsides of that strategy going in.

To take another example, unless it is to be professionally managed after death without family involvement or interference, a Foundation is something that would only belong in a Growth scenario plan.[7] If the Foundation is going to be managed by the family, it requires a host of skills that need to be presently evidenced and further developed in the rising generation. Failure to discern these capacities accurately is likely only to institutionalize functional or dysfunctional family patterns.

Turning to the endgame of Division, estate taxes are often due. This can be painful for a client to contemplate. On the other hand, paying those taxes gets the government out of the family’s affairs quickly. Setting up a series of structures that continue to hold assets means that the state will be acting in loco parentis through the structures and advisory network (by way of tax law and legal compliance) for as long as those structures exist. Moreover, Division may decrease the relative length of time the family will be dealing with the “voodoo of inherited wealth”. In many cases wealth will wreak havoc for a generation or two, but then it is over as the family will have transitioned back to the middle class. While it is the current fashion for clients to talk about leaving their children limited funds and giving the rest to charity (a plan that seems to be more talked about than practiced), rarely is the endgame of Division (and its implications) fully explained to clients at the front end. If clients truly understood the this endgame, they might make different estate planning decisions.

In sum, most first generation clients don’t know how to think deeply about the implications of the decisions they are making – they are told that they should avoid taxes, and they take that advice at face value. Perhaps if they knew the likely scenarios, the consequences, and the alternatives, they would make different choices. If the planner is guiding the client into a game of Advisory Preservation, it is important that a client knows that explicitly and weigh the consequences of such a plan. If Familial Preservation or Growth is the desired outcome, then the client must at least understand the work required to make that a realistic possibility. Advising from this more elevated strategic perspective is more satisfying for the planner and results in better plans.

The Implications for Planning

All of this resolves into a very simple framework for approaching the planning process.

Fist, the advisor would help the client become aware of the different endgames to the accumulation of wealth. The planner, together with the client, would determine whether the client is basically committed to an endgame of Division, Preservation (with the sub-choices of Advisory or Familial) or Growth. If the client were inclined toward Familial Preservation or Growth, the advisor would explain what is required for these to be successful. For the rising generation this would involve the intentional development of the five wealth competencies (financial, wealth, governance, business, and philanthropy). If the family is demonstrating the nascent capacity to engage in Familial Preservation or Growth, the client would be coached to invest the time and money necessary to develop a family culture robust enough to serve as a sufficient counterweight to the Formation being created by the estate plan.

Second, the practitioner would ONLY advise the implementation of those estate strategies that tactically align with the client’s desired endgame. The advisor would think about various planning structures he or she uses in terms of their suitability for particular endgames. Dynasty trusts would not be put in plans implementing Division scenarios. GST trusts could be established in Preservation and Growth scenarios, but would have different governance structures based on the endgame being played. In Familial Preservation and Growth Scenarios, the family would be given more control over the governance of the GST. In Advisory Preservation scenarios, professionals would be given control. Family Banks would be found only in Growth scenarios where the family culture was equal to utilizing them effectively. Private Trust Companies would be available options in Preservation and Growth scenarios but with the caveat that the family is equipped to govern these in Familial Preservation and Growth strategies. If the PTC would be professionally managed in an Advisory Preservation strategy, the family would be given less power, information flow would be limited, and controls tightened. Family business or enterprise succession would only become part of plans where the family is committed to a Growth scenario and had the capacity to execute on that strategic outcome.

Congruently, the drafting of various structures would shift based on the endgame they were supporting. A trust might be created in a Division scenario where a client couple wanted to ensure that all of their grandchildren received a college education to get a good start in their adult life. Such trusts would have quite limited distribution provisions, not the usual HEMS standard. They would contain sufficient capital to fund education and would then terminate with the expectation that the grandchildren would rise or not based on their skills and abilities. In such plans trusts would be independently structured and capitalized based on the purpose of the trust. Education trusts would look different from Health Trusts which would have very different provisions for whatever trusts were established to support lifestyle (Support and Maintenance trusts).

Advisors need not become experts in qualitative outcomes – only the rough outlines of the likely outcomes of various plans. Of course, final decisions are up to the client, but to approach planning from a strategic point of view of the basic endgames of wealth gives the advisor a heuristic both to explain options to clients in meaningful ways and to design and draft documents that are more consistent with those strategic outcomes. Advisors who are attuned to these issues will be less likely, for example, to advise clients to set up structures in cases where the family has evidenced little or no behaviors that make it plausible to believe that it will work or actually benefit them individually or collectively.

A Final Word About Growth

When I speak with wealth creators, few are interested in creating a “dynasty.” Most often they simply want their children to be happy, competent and caring. They want their families not to split apart because of the wealth. They want their grandchildren to thrive. Ironically, the things they hope for are the things that are requisite to sustaining wealth in a Growth scenario. The scenario requires happy, successful siblings and cousins who work together for the good of the family as a whole and the communities in which they live. It requires responsible stewardship and the ability to make good decisions. It requires the development of personal and interpersonal skills. It requires keen minds and open hearts. It requires real work and acumen. The Growth scenario is dynastic by its very nature. Only flourishing families can sustain a family dynasty. Perhaps by throwing away the option of thinking dynastically, wealth creators are dismissing the very thing that has the highest potential to produce the outcome they most want.

It is true that few families are truly capable of operating under a Growth scenario. It requires intent, focus, and good leadership to create the kind of familial culture that will support Growth. For those families that commit to this path, the financial and personal rewards can be high. Often, however, whether a family is truly in a Growth scenario or they are in a Familial Preservation scenario only becomes evident in the third generation.

Conclusion

While the approach advocated here is not a silver bullet by any means, it seems to be an improvement on the present system. A great deal of heartache and familial difficulty would be avoided by tailoring plans not to the tax code but to the educated and informed intent of the client who takes into account the capacities, skills and intentions of the family. Families that are capable of growth would be given the tools they need to be successful and the authority to use those tools effectively. Families not capable growth would not be burdened with massive formations and their inevitable advisory networks they are neither equipped nor willing to manage. Clients would gain much greater clarity on what they need to focus on in preparing their children for the wealth and how best to communicate with them. Children would be clear on where they stood and what was expected of them with respect to the planning and preparation for receiving wealth. More importantly, these rising generation family members could have meaningful input into those plans on a strategic design level particularly in Growth and Familial Preservation strategies. Indeed these two strategies are not truly viable strategic options if the rising generation does not support those outcomes and is not involved in their design.

*****

In our final installment, we will look at the conditions that must be in place to make Familial Preservation and Growth viable options for clients and what advisors need to know to help their clients make these determinations.

Notes:

[1] My current thinking is that there are “healthy” and “unhealthy” versions of these endgames. In this piece I will explore only the healthy and unhealthy versions of Preservation and leave the other two for another time. As a preview, unhealthy Division would be giving heirs assets outright for which they are not prepared – like giving a 16 year old the keys to a Ferrari. Unhealthy growth is harder to find, but it would revolve around forcing people into unwanted familial partnerships. In my experience, the “half-life” of unhealthy Growth plans is usually short – they quickly give way to games of Division in the form of legal disputes.

[2] I am indebted to George Marcus for inducing me to the notion of formations – a term he developed in his ethnographic studies of wealthy families as documented in Lives in Trust (1992).

[3] The ambiguity as to whether the advisor is serving the family or the structure here is deliberate. Advisors often have a vested interest in the perpetuation of structures, as justified by the founding documents, which can create its own series of tensions and even conflicts of interest. Too often estate plans are designed to effectively ensure that the advisors’ primarily allegiance is to the perpetuation of the legal structures rather than the deeper well-being of the individuals within the family. Ironically, the greatest threat to the endurance of the structures are the people they were purportedly designed to “benefit.” Such structures, so designed, are inherently sclerotic – to borrow a term used frequently by my dear friend, Jay Hughes.

[4] Bingham, Sally, Passion and Prejudice: A Family Memoir (1989) pages 336-337.,

[5] Note that the advisors do not work for individual beneficiaries. It is important to understand this distinction.

[6] What we mean by this is that the organization is preeminent over the familial context in which the entity is embedded. For example, few such plans are collaboratively designed on an intergenerational basis – they are not collectively created but designed behind closed doors. One of the seemingly necessary corollaries of adopting a Family Preservation or Growth plan would be that the adult family members be intimately involved in the design of that plan – that the hard reality of collectively is itself addressed in the planning process. No such involvement is necessary for a Division or Advisory Preservation plan.

[7] This will be controversial, in that a small Foundation could be considered a “training ground” for the family to manage the patrimony. However, a large foundation will dilute the capital to be preserved and there are likely better ways to empower the rising generation to work together. In Growth families foundations serve multiple purposes including the development of social capital, business development opportunities and strategic connections to hard ROI as well as the development of the rising generation, the formation of family identity and the doing good work in the world. Whether a Foundation is a proper instrument in a Family Preservation scenario is, at the very least, a question worthy of real strategic consideration and clear design.

— May 6, 2016