Lost in Translation

There is some controversy over which German psychologist first said, “andere als die Summe seiner Teile ist das Ganze.” Some report it was Wolfgang Kohler. Some say Max Wertheimer. Others, Kurt Koffka. All were experimental psychologists at the Psychological Institute in Frankfurt between 1910 and 1913. With several other psychologists (collectively known as the Berlin School), Koffka, Wertheimer, and Kohler were founders of Gestalt psychology.

Not only is the origin of the quote in controversy, so too is its translation. Most Americans have heard the phrase translated into English as “The whole is greater than the sum of its parts.” The sloppiness of this rendering irked both Kohler and Koffka. The better translation is “the whole is other than the sum of its parts” or to, make this less strange to ears accustomed to English, “the whole is different than the sum of its parts.” The heart of their objection to the mistranslated phrase lies a rather insightful recognition that, in quintessentially American fashion, we turned a fundamentally qualitative observation (“different” or “other”) into a quantitative observation (“greater”).

Our translation truly missed the point.

Why should this obscure controversy over the translation of some German phrase at the heart of Gestalt psychology interest us as family advisors? I would submit that this small mistranslation yields a critical insight central to the nature of family culture and how we, as professionals, work with them.

The Groupness of Groups

In the West – and particularly in the United States – we are accustomed to working with individuals. Our clients are individuals, each with individual needs and aspirations. We focus intently on those needs and seek to meet them as best we can. The broader culture reinforces this lionization of the individual, emphasizing the self-made man, standing on one’s two feet, and rugged individualism. Studies show that there is a high societal premium placed on independence, individuality, and differentiation in the US in particular.[1] Even when US advisors work with couples or groups, they tend to see a collection of individuals whose interests and perspectives must be compromised and blended into a common set of objectives.

This phenomenon is so ingrained we don’t even notice it. When people raised in the US are shown a picture of a group of people, studies show that they focus on individual faces, one at a time, and draw conclusions about the individuals in the photo. By contrast, when people raised in Japanese culture are shown the same picture, they focus not on individual faces but also on the group. They initially pay a great deal of attention to the social nature of the photo and try to determine the group’s qualities and the way each person is connected to the others in the social matrix.[2] One way to see these cultural differences is as a contrast between focusing on the figure (or particulars) and the ground (or context).

The Bias of Individualism

This deep bias in our Western mindset to individualism colors our work with families. We tend to see family systems as a complexity problem brought on largely by the accretion of individuals and their interactions as individuals (i.e., we see these dynamics as a quantitative problem). The larger the number of people, the greater the complexity. As more individuals are brought into the group, the complexity increases as a function of sheer numbers (because the whole is “greater” than the sum of its parts). For example, the addition of new spouses, in this model, adds to the complexity of the family system. The problems of families come to be seen as a function largely of how individual members relate to other members, as reflected in their multiple interactions. The aggregate of these interactions is seen as a “family system,” with the interactions being called “family dynamics.” We tend to see this dynamic system in terms of “collectiveness” without ever seeing what might be called “groupness” apart from that collection of individuals. In the end, we are blind to the family grouping as an essentially distinct phenomenon from the collection of individuals who comprise it – or, in gestalt terms, we don’t see the family culture as being other – or qualitatively different – than the sum of its parts. This insistence on “greater-ness” rather than “other-ness” creates problems.

To illustrate, last month I was working with a family and one of the family members said to me that she would often be brought to tears in family meetings. She disclosed this with an obvious bit of sheepishness and was clearly embarrassed by her emotional reactions in her family. I asked her if she ordinarily cried in meetings she attended in her daily life, even when her emotions ran high. She said that, of course, she didn’t. I suggested to her that this probably meant that her tears, in an important sense, were not her own – that her individuality was being “hijacked” by the group in ways that made her individual responses “other” than what she ordinarily experienced – she had reported that she quite literally felt that she was “not herself” in her family. I hear and see this a lot in the families I work with. It turns out that the group actually uses the individual to some functional purpose of the “whole” and in many ways quite independently of the individuality of the person involved. In this way, the group is qualitatively “different” than simply the accretive collection of individual personalities and their reactions to one another. This can be seen as a classic case of the whole being “other” than the sum of its parts (with that “otherness” being manifested in one person at one point in time).

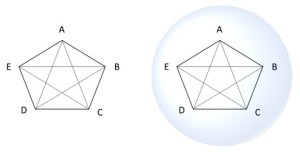

The following diagram attempts to get at least one aspect of what I am speaking to here. The diagram on the left represents a kind of elementary systems thinking. The five letters on the outside of the pentagon represent individual family members. Causal links are reflected in all the various lines of communication and relationship. In this diagram, the whole is clearly greater than the sum of its parts – the lines between the individuals show a complex matrix of relationships, but the system as a whole can be analyzed within the “five corners” of the pentagram. This represents a very rudimentary form of “systems thinking” (we could add lots of feedback loops, dependencies, processes, and causal chains, but that wouldn’t subvert the point here).

In the second diagram, the sphere represents something quite different – the sphere is “other” than the sum of the pentagon’s parts and even the complexity of their relationships. Instead, the sphere represents a “field” in which the system exists. It is a concrete representation of what we might consider the subtle field of “culture.” If the diagram were of a family, the sphere would likely be felt but not clearly defined or seen. It would be the “air” in which the family acts. What is not clear from the diagram is that this “field” of culture has a great deal to do with how the parts arrange themselves. That there is a pentagon – and that it is in this shape rather than a circle or some other pattern is, at least in large measure, a function of the unseen “sphere” of culture.

The problem, however, is more insidious than this. The definition of the sphere in the second diagram created an object that you can focus on – it transformed “ground” into “figure”. In fact, culture is much more like the screen or paper “in” which the diagram (without the sphere) appears.

Turning away from the diagram’s concreteness to this particular moment you are experiencing now, culture led you to read this blog, what allows you to understand it, what creates your interpretation of its meaning, and what shapes your internal reaction to it. If I had simply posted the diagrams, they would have made no sense (or more accurately, you would have drawn a purely private – non-cultural – conclusion about their purpose). The diagrams make sense to both of us because they exist in a context. One context is the blog piece itself, but there are much larger contexts in play. If you did not speak English, it would make no sense. If you were not educated to understand diagrams, it would make no sense. If you were not sensitized to the issues it addresses, you would have passed it by. These are all things that you absorbed from what we call “culture” and, indeed, “sub-cultures.” These are all things that reside “in” you in some meaningful way, but more importantly, they reside “between us” in what might be called “inter-subjective” space. In this sense, these exist within the “field” of our imperfectly shared culture. I would not have been able to create the diagram or this piece without complex dynamics associated with the various “cultures” to which I have belonged directly or by proxy. You would not understand it if we didn’t share some of these cultural roots. Indeed, it is culture that determines your experience, my experience, and the meaning you and I make of that experience. It is the “water” in which we swim. And 99.9% of the time we pay no attention to it and, even when we do, we have a very difficult time seeing it. This is why we all find culture so difficult to describe and particularly define with any type of precision.

The interesting thing is that this notion of “fields” is only now emerging in the collective zeitgeist as a way to understand human interaction.[3] There are very few professions that have as a domain of expertise paying attention to this complex dynamic. In academia, this is the domain of anthropologists, sociologists, linguists, social philosophers, and others. In the professional world, there are even fewer who work with what we are calling cultural fields.

The Behaviorist Approach

To use our diagrams as a reference point, psychology and other forms of therapy (for the most part) focus either on constituent parts of “the pentagon” (the individuals) or on the pentagon itself (the system). Some do a deep dive into the psyches of individuals in systems (and trust that change within A, B, C, D, or E) will change the dynamics in play in the pentagon (good examples of which are individual coaching and therapy). Others work on the relationships between A, B, C, D, or E in systems interventions (a good example are therapists who work with family systems). This is all good, important, and even necessary work. But it is not directly focused on the social “field” itself – and the effects on the “field” are indirect or even mostly coincidental. The theories of change underlying these interventions presuppose that transformation happens “in” and “between” individuals through causal chains of internal realignment or external shifts in interaction.

This behaviorist approach typically treats the family system as an accretive entity. In this therapeutic world, the whole is greater – not different – than the sum of its parts. Behavior in human systems is treated as a complexity problem with the complexity residing either in the individual or in the group dynamics. Thus, if one can change the parts (and/or the interaction between parts), one will change the whole. To come back to the woman who cried in family meetings, the behaviorist would most likely focus on the crying and attempt to get to the bottom of the emotional dynamic that created the tears and then create better coping mechanisms for the family members to address their communication with one another. Alternatively, some would see the tears as a functional component of the system as a whole and seek to alter the system so as to address the “cause” of the crying (often the disowned parts of the system). Individual authenticity, communication and trust would become the name of the game and people would be encouraged to become more self-aware, transparent and authentic with one another.

However, just as culture eats structure for breakfast, so, in my experience, culture has the power to twist psychology into pretzels.

This is not to say that psychological work is not important or even critical to success. I am personally a fan of various theories of family dynamics and depth psychology. These are clearly an important “part of the game” in working with families. The same is true for the structural work we explored in the last post. It is just that, like structural work – therapeutic and systems work is not sufficient and perhaps not even primary in working with client families. Every family I have worked with has intuitively recognized this issue. They do not want to get lost in the world of “process” or “woo-woo” or “touchy-feely” stuff. They sense intuitively that –by itself – therapeutic work will become a black hole that will not allow them to sufficiently progress to desired outcomes. Some advisors’ response is to gloss over or downplay this concern and bring their expert opinion that the work to be done is to focus on clear communication, understanding of one another, and the development of trust. These advisors are fond of saying that the number one cause of failure in wealthy families lies in failures of communication and trust and that if families fix their dysfunctional patterns, things will get “better.” They are right in one sense, but, from where I am sitting, they have confused observable effect with the root causes that are far less tangible.

In my experience, breakdowns of communication and trust are, in fact, symptomatic of larger problems that exist within the “fields” of family culture – they are epi-phenomena of a deeper, less obvious set of cultural issues. Work attempting to create “trust” or “better communication” (addressing symptoms) will ultimately prove ineffective because the core problem is not resident in these issues. (This is not to say that some work on better communication skills and trust-building are not important and even necessary – only that they will not be sufficient in themselves to shift-long term outcomes.) Thus, when families are leery of process approaches that are grounded in behavioral theory, my sense is that families, not the experts, actually have it right. These families understand that the purely psychological path is, in the end, a black-hole of endless process. Working on communication and trust, and even family dynamics will not get them across the goal line. They rightly suspect that they will become mired in relational quicksand.

Those consultants who come armed with behavioral solutions will most often find themselves stymied in the practical complexities of their families. These families need something other than what the behaviorists offer. Consequently, their good work fails to find sufficient ground in the gritty realities of what families have to deal with. While structuralists tend to fear emotional dynamics in families, behaviorists tend to overestimate their importance.

Interventions in the Cultural Field

To illustrate, one common approach used by many consultants is to help people understand one another’s communication style or personality type through an assessment. The theory is that once I know where you “are” in, say, the Meyers Briggs typology, I will be able to understand both myself and you better and, with that understanding, some element of compassion will naturally ensue. To some extent, this seems to work. The approach messes with the “accounts” individuals have of other individuals in the group. For example, it moves a statement like “I think you are a jerk” to “Now I understand that you are a jerk because your communication style is different than mine and that actually your style might be useful to us as a group because it provides a different perspective.” However, it does little to truly address the underlying issue of “jerkness” and the causes and consequences of that jerkness within the family system. The “problem” is seen as resident in the person or the system (i.e. it lies within the pentagram) and the assumption is that some form of “change” is required to make the system more “functional.” Usually, this involves asking the person who is a jerk to be less of jerk or for others to be more understanding of his jerkness – in other words, it is asking people to change. And we all know that change is difficult. The added level of explanation can shift the family narrative a bit, but it doesn’t ultimately change group dynamics. In this example, the jerkness is still a problem, and while it is incrementally reframed, it only marginally affects the family culture. It is a small move in the right direction because it changes the meaning or story, or account of the group. However, it fails to substantially alter “culture,” which is the force that fundamentally, if invisibly, shapes the interaction. In terms of our diagram, it plays within the corners of the pentagon, not in the sphere.

I would suggest that in the hands of a skilled culturalist, the real shift that occurs through tools such as typologies is not what happens in the individual understandings of other individuals, but rather in a more subtle shift in the group narrative or belief system to one that says “Now that “we” have come to understand each others’ styles, “we” — as a group – have come to be more tolerant than we were before.” This frame allows the “jerkness” to continue, but it now exists in a “sea” or context of socially constructed tolerance and therefore, the effects of the ongoing “jerkness” are different – they exist re-contextualized in a much larger cultural field. This represents a shift not merely in individual psychologies or personal perceptions, but in the collective sense people are making of their common experience – it constructs a new social reality and therefore “changes the game.”

In this model, change has occurred, but it is not a willful behavioral shift by any individual. Instead, it is a semiotic shift of the collective as a whole. It is a shift of the meaning that the group is making of its own experience – and in this sense, nothing has changed but, assuming the stickiness of this new meaning, all sorts of change will cascade out of this new collective cultural redefinition. The power lies not in how individuals see one another but in how the group has redefined itself from a superordinate position as “being more tolerant.” That shift, if it is “real” means that the dynamics of the group as a whole, and consequently the individuals within the grou, are likely to shift as well – individuals will, in fact, act more tolerantly because this behavior remains consistent with the new narrative about the family. The move reduces chaos and elevates the meaning-making capacity of the group as a whole to one of hopeful evolution. “Jerkness” will also likely diminish because it is no longer a culturally relevant behavior and is no longer generating oppositional energy within the cultural field. When these group redefinitions occur, they create a powerful blob-like effect that radically re-contextualizes and even alters individual behavior without anybody having to exert themselves to change their habitual behavior consciously.

The problem, of course, is that group behavior is stubborn and persistent, and until a new narrative is fully embedded, it will be stress-tested to determine if it is trustworthy. Every individual will be asking about this new group story’s validity – are we truly more tolerant, or is this new story a fanciful illusion? Individuals will press the limits of this to determine if the narrative is “true” and “reliable.” The new narrative comes under pressure, and an essential aspect of the intervention by a skilled culturalist is to know how to address and deal with that pressure. If the new narrative falls apart under testing, it will “prove” that this new sense of the group is “wrong,” and the group will fall back into their old ways. The one who is doing cultural intervention has to truly upshift narratives in ways that become “sticky” or inherently “believable”. This process of meaning-making and testing can seem like a long and arduous process – but it cannot be too long or it will fall apart. It requires quick wins, systems of integral accountability measured against the narrative, the creation of new self-reinforcing narratives and story development, and forms of reinforcement and anchoring in decision making, responsive behavior and forward movement in the form of progressive engagement. While this is a central piece of cultural work, it is only one aspect of even more extensive skills in addressing culture.

[1] . Hoffstede Culture Survey

[2] See, Nesbit, Richard, Geography of Thought,2003

[3] For early work on social field theory, see Kurt Lewin, Resolving Social Conflicts (1948).

— March 2, 2015